By Joaquin Culbert | @joaquin.culbert

A chronicler who recites events without distinguishing between major and minor ones acts in accordance with the following truth: nothing that has ever happened should be regarded as lost for history.

Walter Benjamin, On the Concept of History, 1940

“Nothing that has ever happened should be regarded as lost for history.” These words hold true, particularly for those dedicated to the struggle for freedom against a seemingly endless state of institutional oppression on all fronts. Few have felt these effects so keenly as indigenous tribes and nations across the globe, and perhaps due to this, these groups seem uniquely situated to exist at the vanguard of this resistance. Exhibited under the title Moving Forward Together at Presa House are the results of a years-long and still-in-progress research project by Antonio Serna into the histories and materials of various indigenous artists and activist groups operating across the Americas and Europe in the 1960s and 1970s. Presented throughout the gallery are original publications independently published by these groups alongside photographic works by Serna—his own reflections, perhaps, on these aforementioned histories and materials.

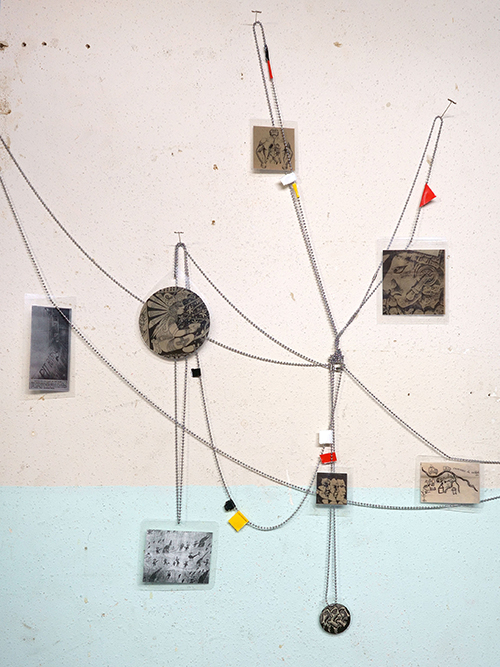

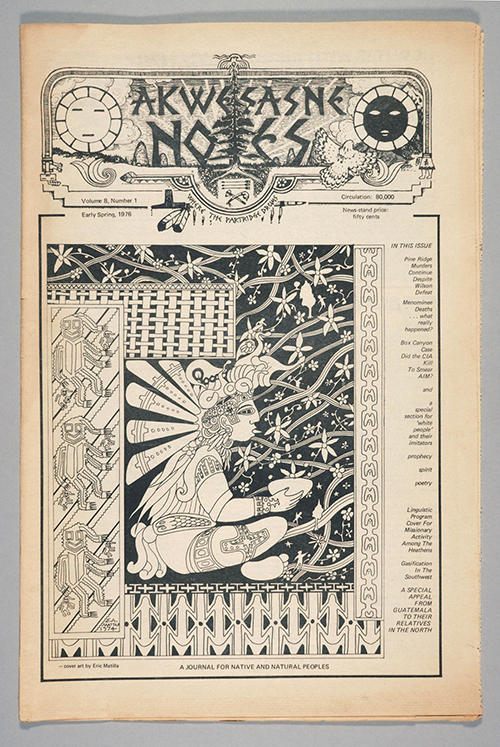

Serna’s photographic works depict reproductions of the original published materials—as tokens or cards—meticulously arranged and strung together using steel bead chains. These tokens and cards serve as reference points, and the chains as linkages between these points, which, however ambiguous they may seem at first glance, establish visual connections that allow viewers the necessary structure and space to develop their own associations and narratives upon consideration of the work. The presentation of these works in the gallery space reflects, in a certain sense, the visual arrangement of the material in the photographs, enhancing the immersive quality of the exhibition. Furthermore, inserting specific graphic illustrations serves as one linkage, connecting anthropological and indigenous activist journals across continents. One recurring image found in the works is the Piaroa woman and child included in a “Slaaf of Dood”—”Slave or Dead” in Dutch—graphic.

Additionally, throughout the exhibition, one comes across an image of a Yanomamo man aiming his arrow upwards, an illustrative reproduction of an anthropological photograph seen in numerous publications. The recurrence of these images or slogans throughout the gallery enables viewers to take on the role of researchers, mirroring Serna’s process and bringing this to the forefront of the viewing experience. The works and the original materials are densely packed with information and deserve detailed study that rewards the insightful viewer. Flashes of truth and meaning can be briefly grasped when walking through the exhibition, and it is from this that the viewer can come away with some understanding of the importance of this work.

By looking back and reflecting on these nearly lost histories, Serna propels himself forward and beckons us to do the same.

Some publications of particular prominence in the exhibition are the Dutch and English version of Slave or Dead from the Netherlands, two versions of Supysaua, one from Brazil and the other from Berkeley, Akwesasne Notes in New York, and the Indigena newspaper out of Berkeley. As such, some of the exhibited research and publications are centered around several tribes along the Pit River and Hupa Valley in Northern California and the Orinoco River Basin in the Venezuelan and Brazilian Amazon. The Yanomamo, Makiritare, and Piaroa tribes of South America, in particular, are highlighted throughout numerous works. Additionally of note is the integration of Mesoamerican imagery appearing in various publications, further contributing to this sense of tying together or unifying the unique situations and struggles of indigenous tribes across the Americas.

These original reference materials, publications, and other ephemera—oftentimes the only documentation of various activist happenings and events from the era—were borne of a certain necessity. The artists and activists were responding to a state of widespread marginalization and oppression (that continues today) and responding against it in an attempt to counter it. They self-published magazines and journals, staged protests, and organized across continents. It was a belief in the process of actualization that propels this original activism. Serna furthers this, though in a somewhat different capacity. By looking back and reflecting on these nearly lost histories, Serna propels himself forward and beckons us to do the same. Essential to Serna’s exhibition is its unfolding and developing nature. His work is neither comprehensive nor intended to be. Serna’s refusal to make an authoritative statement on these allows the work to exist as a complex web of potentialities and actualities. It exists not as a didactic call to action but as a somewhat guarded invitation. Laid bare, however, is the necessity of forging a new future, and contemplation of these radical histories can allow us to do so.

working primarily with ephemeral materials from events largely written out of twentieth-century history, Serna certainly does not see these events as minor or insignificant but as cornerstones in the generations-long struggle for freedom from oppression and exploitation.

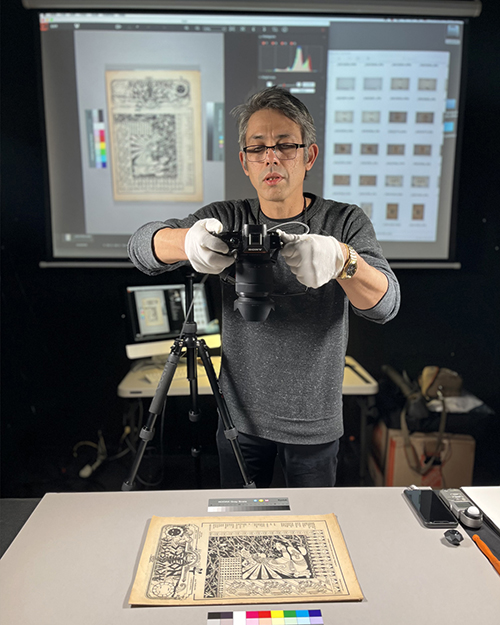

In this manner, the artist subtly inserts himself into this lineage or history. Many of Serna’s photographs were taken in Taiwan, where the artist and his family live for part of the year. We see the hands of his wife (who is Taiwanese) holding up many of the reproduced reference materials, prodding the viewer to consider the particular significance and meaning this research holds for the artist as well as the significance and meaning they can hold for ourselves. And more to this point, the very visual arrangement of the objects, so deftly handled, is itself a gentle insertion into this ongoing narrative. (As an aside, Taiwan has its own history of colonization and indigenous oppression, and though, outside the specific scope of this exhibition, one can’t help but consider the particular histories of the Austronesian peoples in relation to the status of American indigenous groups.)

And though working primarily with ephemeral materials from events largely written out of twentieth-century history, Serna certainly does not see these events as minor or insignificant but as cornerstones in the generations-long struggle for freedom from oppression and exploitation. He is not entirely alone in this; indeed, many of the publications he pulls from have been in the process of digital and physical archivization. The University of California, Berkeley, a locus in the 1960s for many currents of radical activism, houses one such archival collection. However, Serna’s Documents of Resistance Archive will naturally evolve in its own and different manner. Serna is not tied to any institutional apparatus, and his archival work is ultimately and primarily that of an artist, therefore allowing him the freedom to develop the project organically.

For the purposes of the exhibition, there is no concrete need to differentiate between those original publications and materials from the latter half of the twentieth century and those works produced by Serna. Exhibited alongside each other, they all function to create the sense of a project that is still underway, transcending temporal boundaries and encompassing those activists working decades ago and those working today. The artist is included among them, and so are we. For this reason, the exhibition acts as a reminder: it is only together, with an eye to the past, that we are able to move forward in hope and strive for a future of our own making.

Antonio Serna: Moving Forward Together is on view at Presa House Gallery through February 17, 2024. The Closing Reception will be held Saturday, February 17, 2024.

Edited by Rigoberto Luna. Photos Courtesy of the Artist and Presa House Gallery.