By Alex Casso & Rigoberto Luna | @capitalsuspect & @8190luna

Marco Sánchez’s exhibition, Miscelánea Fronteriza at Presa House Gallery, depicts the matrix of religion, history, and social status that shape and influence border cities’ unique position as gateways between countries and for cultural exchange. His artworks are the visual descendants of the Spanish, Mesoamerican, Mexican, and American cultures colliding. The exhibition’s title, which roughly translates into “miscellaneous things along the border,” further illustrates the conceptual point of the border as a kaleidoscopic amalgamation of cultures. Sanchez creates narratives with sympathy, tenderness, sorrow, tragedy, violence, and heroism and guides the viewer towards a pathos for the stories, the people, and the complexities experienced along the border.

Sanchez, a native of the Borderplex, creates art inspired by a deep understanding of its history as a continuously militarized and political flashpoint. Still, for an outsider, a brief overview of the region’s history will help enrich their knowledge and provide a lens from which to view it. Along the border, there is a common feeling that it is neither the United States nor Mexico, but simply “the border” – “ni de aqui ni de alla,” or “neither here nor there.”. Citizens here have dual identities; Sanchez compares the experience as being a child of divorce. Commonly referred to as La Frontera, the border is the literal and metaphorical bridge between the two countries and their histories. Border cities are known as sister cities, two cities related by trade, culture, and family. In Laredo, for instance, there is a yearly ceremony called the Abrazo (hug), where young dignitaries from each city embrace each other in the center of the bridge. The embrace signifies and renews the shared history and friendship between the sister cities.

The border bridges and railways are economic arteries for the US and Mexico. The imports and exports of consumer goods are critical for the prosperity of both countries. While the border still functions commercially, the social dynamics of the sister cities, which provide the unique identity of the inhabitants, have been negatively affected by the escalation of drug trafficking, violence, militarization, and politics. The drug war has had a significant impact on the safety of border communities, which are marked by high levels of cartel-related violence and crime. Kidnappings and murders are frequent as rival groups clash to maintain control over crucial entry points and smuggling routes into the United States, destabilizing local areas and increasing the presence of law enforcement.

The war escalated in the early 2000s, unleashing a torrent of violence along the border. This period in border history coincided with the rise of the internet and the widespread use of smartphones, allowing for unprecedented documentation. The cartels exploited this new era of technology by publicizing their crimes, including the kidnapping and torture of a multitude of Mexican citizens and journalists. Growing up along the border during this era, meant you likely witnessed or experienced some aspect of this violence. Meanwhile, the media and politicians manipulated the border by shaping narratives to sell papers or sway public opinion, leaving the local communities caught in the crossfire as in all wars.

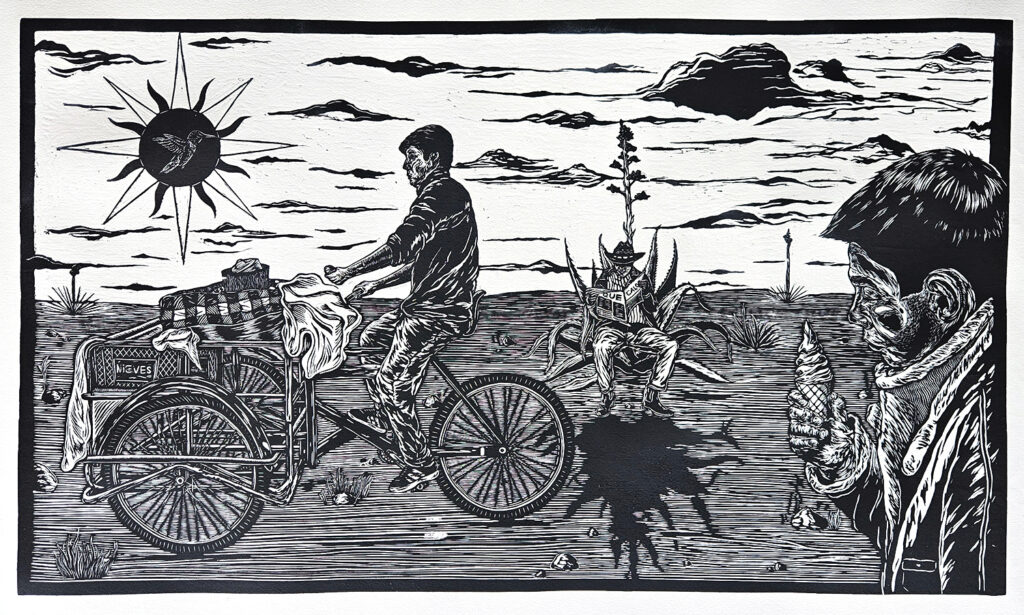

Marco Sanchez’s Heads or Tails, Un Volado en La Línea (2020) draws inspiration from Jason De León’s book The Land of Open Graves, which exposes the suffering and deaths that occur daily in the Sonoran Desert of Arizona as thousands of undocumented migrants attempt to cross the border from Mexico into the United States.

De León’s work documents the experiences of people who have made multiple attempts to cross the border, sharing the stories of the objects and remains they leave behind. The first-person accounts from survivors emphasize the severe risks to human rights and the lives of non-citizens.

In Heads or Tails, Un Volado en La Línea, Sanchez references these themes of chance and peril in the lives of border crossers. The title alludes to the uncertain nature of their journey, much like the flip of a coin. This metaphor underscores the success of deterrence through enforcement and the probability of a border crosser being apprehended by the Border Patrol, depicted here as a 50-50 chance.

The artwork features a shirtless figure, portrayed by the artist himself, suspended in midair between the border wall, the mountains, the ground, and the sky. The sun’s rays create shadows on the ground through the bollard-style wall. The figure mirrors the contours created by the forced perspective of the border wall meeting the mountains in the distance. Three telephone poles are visible on the right side of the image below the figure’s barefoot. The figure in the artwork is intentionally missing his shoe and shirt, referencing De León’s book and the personal belongings, such as bags, wallets, clothing, and religious items, shed by migrants crossing the border.

Through this work, Sanchez illustrates the precarious and dangerous reality migrants face. By emphasizing how their fate often hangs on the flip of a coin, he highlights border enforcement policies’ stark and often deadly consequences. Heads or Tails, Un Volado en La Línea serves as a poignant reminder of the human cost embedded within these policies and the inherent risks migrants take in their pursuit of a better life.

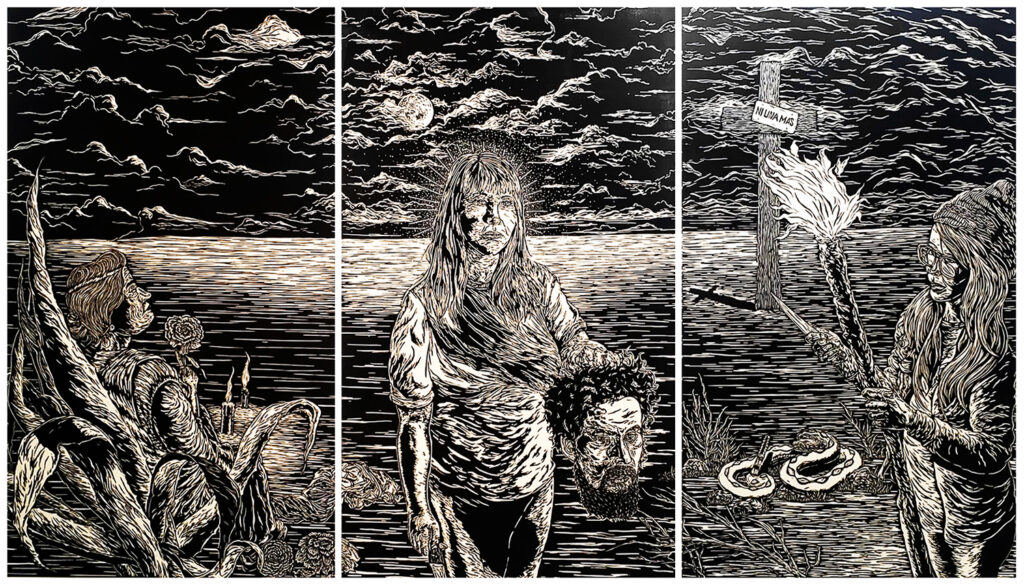

Another powerful artwork about life on the border is the triptych Gentilezas y Rudezas (Kindness and Rudeness). This piece directly responds to the thousands of femicides that have plagued Marco Sánchez’s hometown of Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. The crisis, which began with the tragic murder of 13-year-old Alma Chavira Farel in 1993, has seen over 1,000 women raped, brutalized, and often discarded in the desert or never found.

The artwork’s first impression on the viewer is its scale, the enormity felt through the physicality of printmaking, and your body’s relationship to the work. For Sánchez, this piece is self-reflective, celebrating the sorority and strength of women. It serves as a memento to the incredible and influential women in our lives: our sisters, mothers, tias, and abuelas as a reminder to be supportive of all women.

In the left panel, a woman reclines against an agave plant, staring off into the night sky. The moonlight reflects on the landscape. Unlike most artworks in the exhibition that use sunlight to define contours, this piece uniquely employs moonlight. The woman holds a marigold flower, and a few are visible in the lower right corner of the image. The flower, also known as cempasúchil or flor de Muertos (flower of the dead), is traditional for funerals. Two votive candles sit, one in front of the other, near her base, perhaps to honor a departed loved one, confirming that we are in a state of mourning and remembrance for the deceased. The woman reclining on the agave plant gives clues to further our understanding of the art. The agave plant is regarded mystically in Mexico and is associated with the Aztec goddess Mayheul, the goddess of fertility and nourishment. The agave plant roots the figures to the land and history they inhabit.

In the middle panel, a woman presents a severed head at hip height in her left hand. A knife is visible in her right hand. Clouds partially obscure the full moon, creating a halo around her head. Her emotionless face feels neither remorse nor satisfaction from her actions, and the serene and quiet landscape contrasts with the violent imagery. The woman looks directly at the viewer, while the severed head’s eyes hold the vacant expression of death.

In the right panel, a woman carries a torch and a knife, her body positioned toward the center panel. The knife is rigidly held and pointed toward the central figures. The torch reveals her surroundings, where a defensive rattlesnake on the ground warns of its intent to strike if provoked further. In the background is a cross with a sign that reads, “Ni Una Más”—Not One More. In contrast to the left panel’s observance of the deceased, the right panel embodies a protest for them. Here, the statement gives the viewer the first concrete message from the artist. In other words, Sanchez is saying enough is enough.

Gentilezas y Rudezas references Gentileschi, a 17th-century female artist known for painting Judith Beheading Holofernes (ca. 1620). The Baroque painting depicts a story from the Book of Judith in the Catholic Old Testament, recounting the assassination of the Assyrian General Holofernes. Gentileschi, who often challenged the stereotype of female submissiveness, portrayed herself as Judith, the Jewish heroine from Bethulia. According to the story, Judith, a widow, dressed in her finest clothes and jewelry, visited the enemy’s encampment. Struck by her beauty, Holofernes invited her to his tent. After an evening of eating and drinking, the drunk general fell asleep, allowing Judith to seize the opportunity to take his sword and kill him. Gentileschi’s painting captures the moment Judith, with the help of her maidservant Abra, decapitates Holofernes. The work highlights Judith’s determination to save her homeland and the strength they possessed to overpower the defenseless tyrant in a shockingly violent scene even by today’s standards.

Another artist who famously depicted the story of Judith and Holofernes was Caravaggio. The central panel in Gentilezas y Rudezas bears a striking resemblance to Caravaggio’s David with the Head of Goliath, another of his masterpieces. Like Marco Sanchez, Caravaggio used self-portraiture, casting himself not as the hero, David, but as the villain, Goliath. In Gentilezas y Rudezas, Sanchez also depicts himself as the headless man, drawing parallels to Caravaggio’s exploration of identity and culpability.

The metaphor of David and Goliath—representing the improbability of victory—parallels Marco Sanchez’s story about the plight of women and the femicides occurring at the border. Similarly, Judith’s struggle to save her town of Bethulia in Judith Beheading Holofernes reflects an improbable victory. Both stories symbolize the struggle for justice and the hope for triumph over evil despite overwhelming odds.

The exhibition is full of profound statements. Sanchez created a visual corrido (folk ballad) about people along the border. He chronicles the lives of vendors, migrants, and people who exist anonymously and contribute to the tapestry of border life. Sanchez immortalizes them and expands our perception of the border with messages of strength, dignity, and humanity but they can also be hard truths to swallow. Miscelánea Fronteriza captures the wide-ranging juxtapositions that are a natural result of the border’s living history and multi-cultural inheritance.