By Mia Lopez | @miamia07

What do we try to remember, and what do we long to forget? Two recent exhibitions at Presa House explore the ability of art and art making to aid both artist and audience through the process of recollection. Lauri Garcia Jones: Strangely Familiar and Albert Alvarez: Half God provide distinct yet complementary approaches to navigating personal memories through a publicly accessible medium. Portraiture is central to both Jones’ and Alvarez’s works, not only as a means of depicting people but as a way of giving corporal form to ideas and feelings. Beauty and aestheticization are not prioritized in these uncanny images. Instead, the artists are concerned with reality and candor. Nevertheless, the works they create through drawing, painting, felt, and sculpture lure us into a surreal realm of memory, nightmare, and reverie.

Lauri Garcia Jones creates images of characters she refers to as humanoids, reflecting a hybridity of both humans and ambiguously monstrous creatures. Her figures are primarily flat and cartoonish, calling to mind caricatures with exaggerated features and a technicolor palette. Yet, unlike playful animation or childlike drawings, they convey a sense of melancholy. Jones uses her art to illustrate discomfort, alienation, and a disquieting feeling of gloom. Her works have been a vehicle for her introspection and a space to work through lived experiences she may struggle to overcome. Recalling the adage that “bad things happen in threes,” her subjects, even when complacent, are overlaid with anxiety around life’s twists and turns.

Laurie occasionally does have figures that are surrogates for previous versions of herself, she maintains a degree of anonymity and does not identify those works as self-portraits. Instead, she imbues her figures with characteristics and emotions that deeply resonate with her and perhaps the viewer.

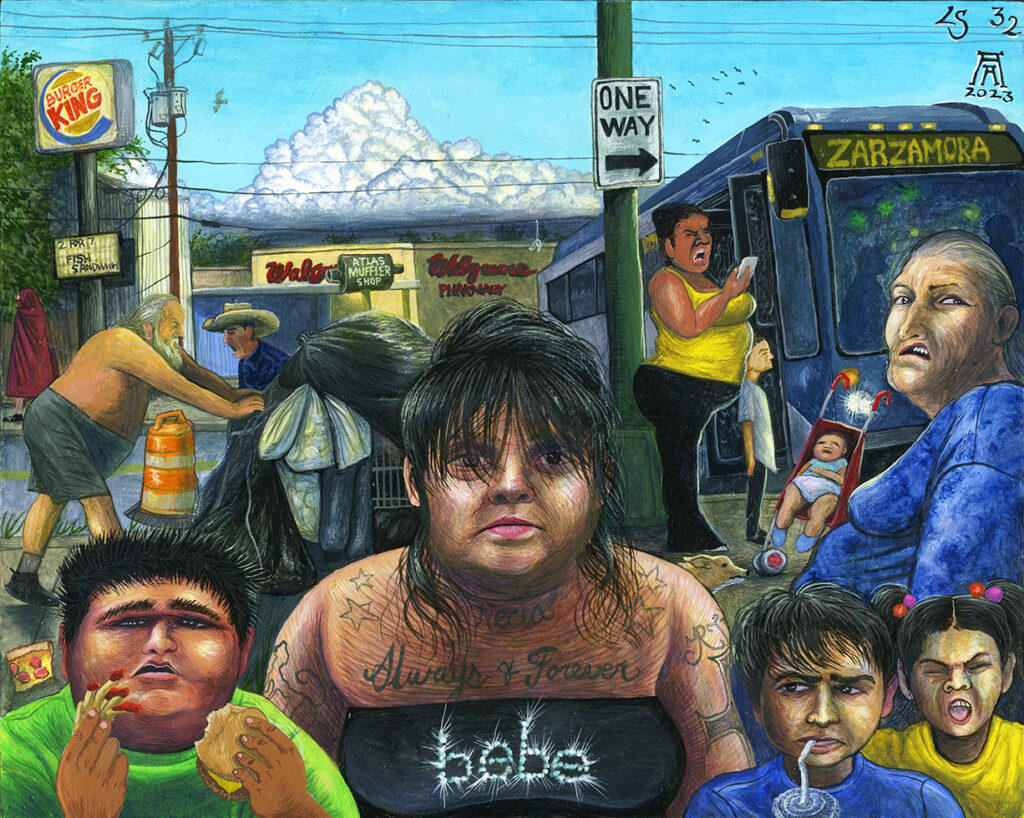

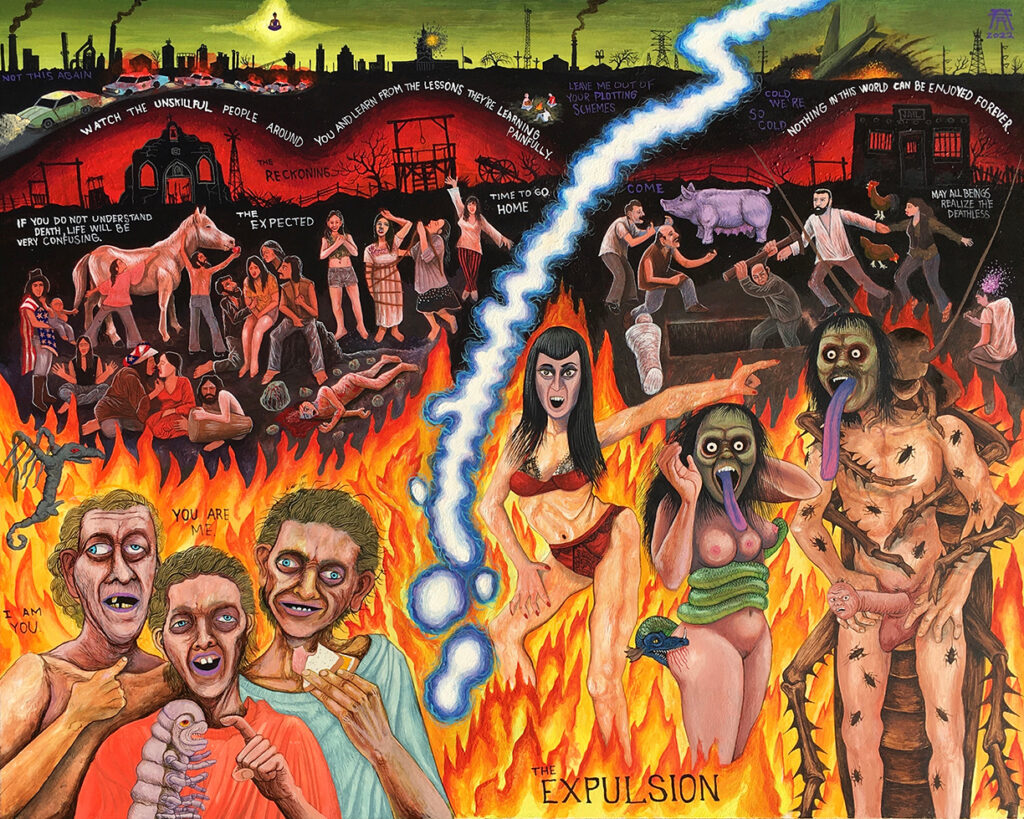

Albert Alvarez meticulously renders detailed scenes of people in typically urban contexts- the street, a city park, a bus stop. His figures are often unremarkable and deceptively benign, representing whatever we might consider normal, at least in San Antonio. Yet these characters are frequently depicted in remarkable scenes that call to mind grotesque fantasy. Orgies, hellscapes, and scenes of anguish and violence are all backdrops for the people Alvarez brings to life. He describes his practice as profoundly influenced by Buddhist teachings and a near-death experience that transported him to the spiritual plane. Alvarez seeks to find reentry to that plane through his paintings and drawings, making visible his spiritual beliefs and the jarring contrast (and similarities) between salvation and suffering. He says his paintings are “safe places to contemplate the harshness and cruelty we subject ourselves to.” Despite the macabre content, Alvarez’s works are nevertheless optimistic, clinging to the belief that this existence, however good or bad, is only temporary.

In some works Alvarez’s figures appear tortured, physically and figuratively, while in others, they engage in debaucherous acts. Yet the artist positions them front and center in his compositions, daring the viewer to find beauty in what might otherwise be deemed repugnant.

Both Jones and Alvarez are loathe to explicitly depict themselves in their work. Instead, they are situated alongside the viewer, witnessing and experiencing the scenes they portray as spectators. Although Laurie occasionally does have figures that are surrogates for previous versions of herself, she maintains a degree of anonymity and does not identify those works as self-portraits. Instead, she imbues her figures with characteristics and emotions that deeply resonate with her and perhaps the viewer. Similarly, Alvarez sets a boundary to enforce distance between his personal life and the world he depicts. He locates the setting for his work as a spiritual plane encountered on the journey towards transcendence. While elements of his native San Antonio often emerge, the people and places he depicts are not necessarily grounded in reality. Says Alvarez, “My compositions use the disjointed narrative structure of dreams and nightmares because this is how the mind reads into perception to find meaning.”

Alvarez is explicit in his intent to force the viewer to look closely at images they might otherwise turn away from. The people he depicts are often in strife, struggling to get by or displaying emotional turmoil. In some works Alvarez’s figures appear tortured, physically and figuratively, while in others, they engage in debaucherous acts. Yet the artist positions them front and center in his compositions, daring the viewer to find beauty in what might otherwise be deemed repugnant. Jones takes an alternative approach to engaging the viewer and seeks to smooth the rough edges of the characters she depicts. Her portraits use felt to soften the impact of what she describes as the harsh and grotesque aspects of her figures. As surrogates for moments of pain and trauma in her life, her humanoids wield less power and potency when rendered childlike and distorted.

Jones often accompanies images of her work with music on social media, playfully associating lyricism with her figures. A clip of Rockwell’s “Somebody’s Watching Me” lends a humorous note to a portrait sketch, whose peculiar gaze is confronting the viewer. In another post, the haunting vocals of Ritchie Valens’ “We Belong Together” accompany a figure with red skin and black hair. The eerie juxtaposition, posted on Valentine’s Day, suggests both Cupid and the devil. Jones’s audio selection for other works includes Janis Joplin, the Beatles, Johnny Cash, Ella Fitzgerald, and David Bowie, presenting a classic soundtrack that underscores the tension between the familiar and the unusual in her work.

The dualities of the attractive and the grotesque, the sterile and the filthy, the despondent and the hopeful are the unifying themes between Lauri Garcia Jones: Strangely Familiar and Albert Alvarez: Half God. The experience of viewing both bodies of work is akin to reading someone else’s diary. To take pleasure (or solace) in this voyeurism, the exposition of deep, dark feelings, may feel indulgent or perverse. Yet this is the artists’ undertaking- to not only give form to their recollections but to make us feel like we remember, too.

Mia Lopez is the McNay Art Museum’s first curator of Latinx art. The new position is funded by the Leadership in Art Museums (LAM) initiative through 2028. The LAM partnership — consisting of the Alice L. Walton Foundation, Ford Foundation, Mellon Foundation and Pilot House Philanthropy — is funding museums to increase racial equity in leadership roles in a manner designed to advance racial equity.

Edited by Rigoberto Luna. Photos Courtesy of the Artist and Photographer Jenelle Esparza.