By Bonnie Ilza Cisneros | @despeinadastyles

There is no savor

Denise Levertov

more sweet, more salt

Than to be glad to be

what, woman.

and who, myself

I am.

Women’s bodies are calibrated, critiqued, confined, condemned, controlled, and when deemed conventionally beautiful, coveted and commodified. Smallness, sexiness, youth, traits of whiteness, and cosmetic enhancements are touted by the mainstream media (a tool of the patriarchy) to convince women they must expend time, money, and energy into forever-fixing and always-improving their exteriors (a boon for capitalism).

It is distracting, to say the least, and dangerous, to say the most. Fatphobia, the fearful disgust some people feel about fat bodies, is real. How fat people get along in the world, how they are depicted in media and art, and even how they love themselves can be skewed by a society who deems fat as a failure, a flop, a flub.

I say they, but I mean we.

Most women have gripes about their physical appearance and work to better themselves, yet there is no hiding a fat body. No pair of black leggings, no baggy sweater, nor neutral tones, nothing quite hides what is underneath our clothes, beneath our skin; la gordura is on view for all to see and judge.

How does fat really make you feel?

When Rigoberto Luna of Presa House Gallery approached me to write about Latent Blatant, the latest solo exhibition by Brownsville, Texas-native Sam Rawls, I learned that Rawls, who is the daughter of a Honduran mother and a Salvadoran father, “embraces fat bodies…and proclaims an unapologetic self-worth,” in her art practice.

In our Venn Diagram, Rawls and I have many overlaps. Tejanas with roots in bordertown Brownsville, mothers of young children, we are women making a life out of art in these very precarious times. Still, our most blatant similarity is that we are both overweight, and we both identify as fat. By claiming the adjective fat, we help neutralize the word’s power.

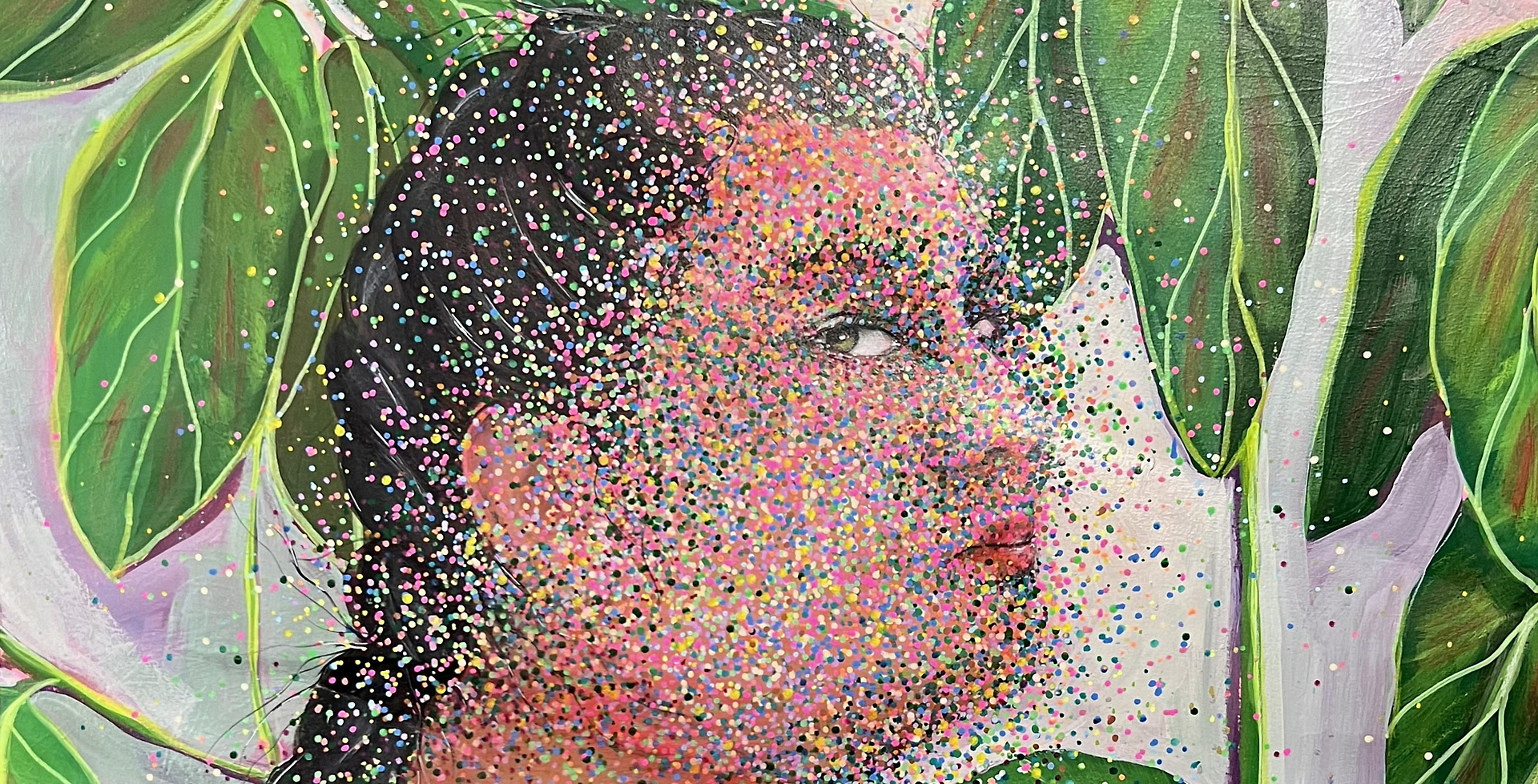

Society demands women battle their bodies into thinness or face the consequences. They tell us to fight fat, be ashamed, and hide, but Rawls’s artwork proposes the opposite. Latent Blatant is a woman claiming space while re-imagining herself within a collection of 26 portraits, many of Rawls herself, and one mobile, a 6’ long chandelier of colorful acrylic cut-outs shaped like various women’s bodies in different poses evoking dancing, stretching, and ecstatic movement. Strands of transparent circles are also suspended with monofilament from hoops hand-woven by Rawls’s mother.

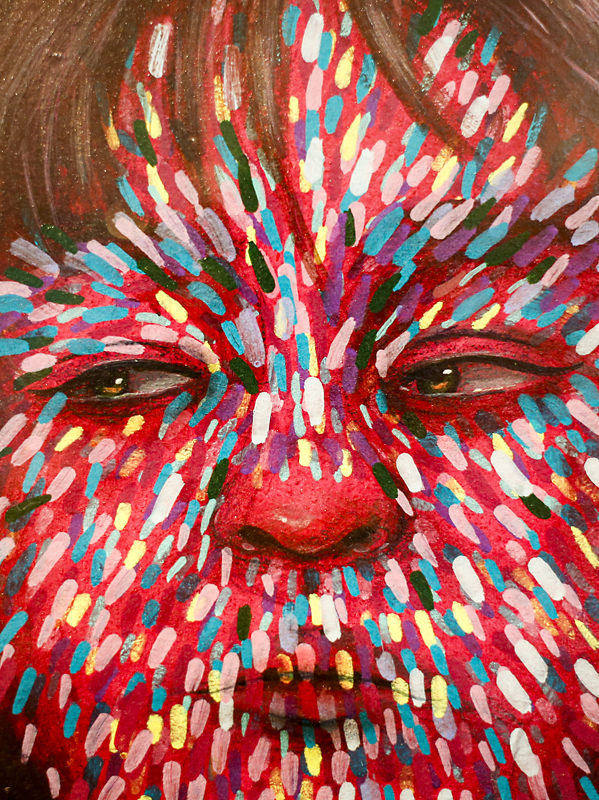

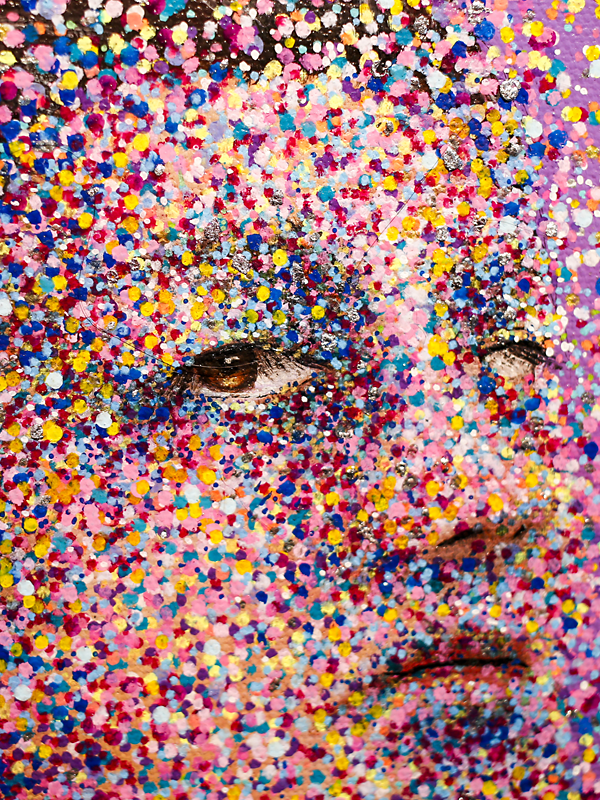

Rawls’s work celebrates bodily forms even while obscuring them beneath cascades of dots or contouring confetti flecks, a process which has become meditative for her. As I stand before her work, I sense that the physical act of pointillism is both instinctual and premeditated, creating constellations, universes, textures, and patterns that illuminate the cuerpos of these women, intentionally masking them, yet enhancing their shapely forms.

“Earth, moon, sun, and human beings all represent dots; a single particle among billions,” proclaims Yayoi Kusama, whose obsession with dots is an immediate connotation for me when viewing Rawls’s work. The more I learn, the more solace I find by tracing the tracks of women throughout time who have made their marks in an art world that undervalued and underrepresented them.

In Mirror Mirror: Self Portraits by Women Artists, Whitney Chadwick writes: “Photographic mise-en-scéne, the staging of the scene for the camera, encourages the production of intricate fictions, diverse selves, dramas of fantasy and desire.” Based on a photograph of Rawls taken by her sister, Un Día Cabre Aqui, is a nude self-portrait.

“I felt I was going in circles trying to validate one’s journey on learning the process of loving oneself and making changes on one’s terms.”

With her hair piled atop her head in a mom-bun, squatted and hunched within the confines of a sandia-red canvas, but making moves to push herself outside its confines, we see a woman wearing nothing but a sheer shade of hot-pink and speckled with multicolored dots that, on the one hand, mask the body’s particular details, and on the other, become an aura of protection. Un Día Cabre Aqui is a fantasy self-portrait of color, curves, and dots.

Here, my gorda-from-the-border self wants to make a reference to cortadillo, Mexican pink cake with sprinkles, but I feel a flash of self-consciousness. Healing is a process, and the urge to predict a person’s fatphobia, in this case a reader’s, maybe yours, and make a fat joke before someone else might, is a coping mechanism I picked up somewhere along the way. Still, I love the celebration of these colors, and the riot of all those sprinkles, and the effect, for me, feels as sweet as pink cake tastes.

Rawls’s tells me Un Día Cabre Aqui is partly a response to detractors who have told her that fat bodies have no place in art because they promote unhealthy lifestyles: “I felt I was going in circles trying to validate my own journey of learning the process of loving myself and making changes on my own terms.”

Rawls’s pose evokes a coiled-up determination to push aside fatphobic finger-wagging, even if the nudity feels strategic, and almost modest. Her face, hands, and feet are free of embellishment, reminding us that a fat body is just that, a body.

The eyes, like in many self-portraits in Latent Blatant, feel really… real. They seem to fixate on me, follow me around the room, like religious icons. When you look into them, they seem to see you. Rawls calls them “las miradas, fixated stares at the viewer,” which she says echoes a common phrase in the Valley: vistes la mirada que te dio?

I can hear the tía in my head interrogating: did you SEE the LOOK they gave you? I know RGV señoras who can express intricate emotions with only their ojos. From portrait to portrait, I feel these eyes staring, and for a brief instant, I think I see my own eyes looking back at me.

Later, I tell Luna how that really never happens. I don’t see me in the museum, nor the magazine, nor the movie, so when galleries like Presa House showcase artists who are from where I am from, who look a little like me, who carry the same weight and who contain similar stories as me, it makes me feel…like art.

How do portraits like the ones in Latent Blatant make you feel?Poeta soy, so I find pleasure in the titles of Rawls’s artwork, and her intricate palabras become prayers: No Hay Crecimiento sin Un Poca de Lluvia, Las Hojas me Acarician Sobre la Piel, Ato Mi Cabello Hasta Que Mis Incertidumbres Estallen. Rawls carefully contemplates titles in both English and Spanish and she relishes the weight words carry, often more so en español: “Son mas pesados, se escuchan mas fuerte,” she tells me, “I am more poetic in Spanish.”

Un Día Cabre Aqui is a poetic and wistful proclamation. I think how aqui can mean “from here,” a common way to label someone born north of the Río Grande, or it may be the literal confines of place, here, where the body takes up space in time. Rawls shares that “one day I’ll fit here” is a phrase, como un deseo, she says when an item of clothing no longer fits: “I am making plans for the future, knowing it may be challenging.”

To fit in your jeans, to fit in society, to fit all the pieces together: mother, artist, human. We are works in progress, always changing, as demonstrated by the flick flick flick of Rawls’s paint marker beauty marks, which for her represent the tenderness of self-care that insists, as Audre Lorde writes in A Burst of Light: “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence. It is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.”

“He allowed me to be an artist and learn about accepting and processing my emotions of this body”

In 2017, Rawls began painting while in graduate school, a new mom fresh out of the U.S. Army, where she served as a military photographer. After giving birth to her son in 2012, Rawls avoided looking at herself in photos and mirrors as a way to cope with her body’s postpartum changes. However, her perspective changed after studying the work of artists Laura Aguilar and Jenny Saville. Their work portrayed women as they are, not shying from their flaws, cellulite, and imperfections. “[Flesh] is all things,” Saville once proclaimed, “Ugly, beautiful, repulsive, compelling, anxious, neurotic, dead, alive.”

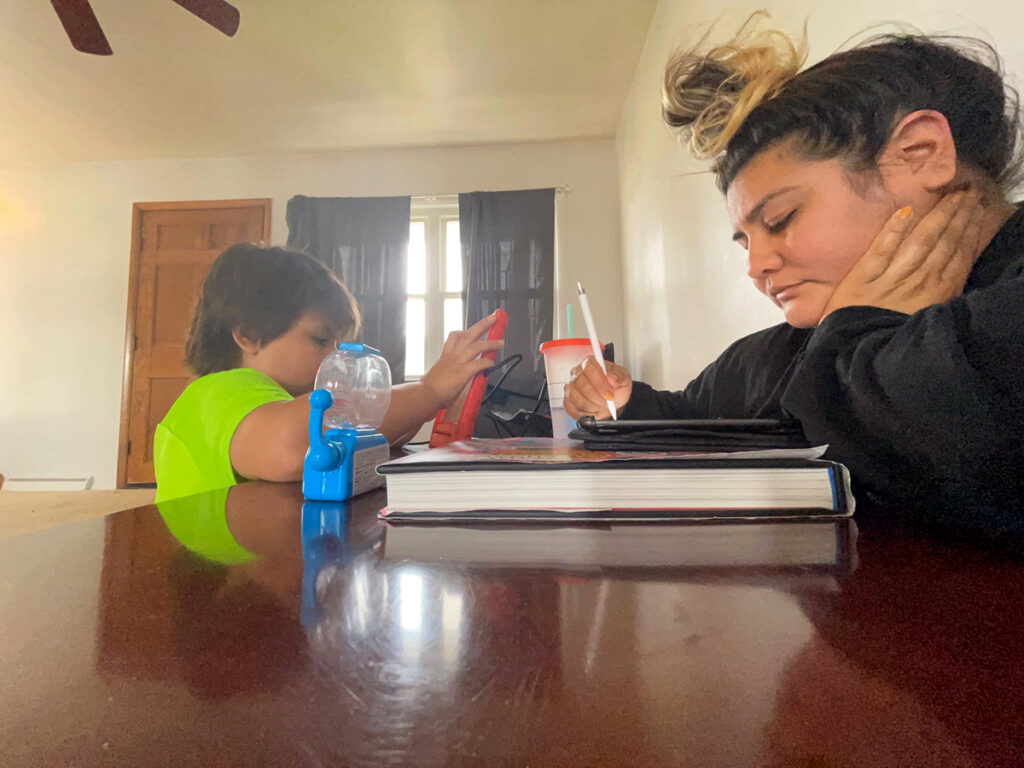

Pregnancy and motherhood are physical processes that alter our bodies and souls. I ask Rawls how being a creator of life (a mom!) can make us better creators (artistas!) and I find it poignant that she learned how to take care of her son concurrently while learning how to express herself through art: “I would sit him with me as I was painting and drawing…he was my subject…[and I] captured the fleeting moments I would never get again. We worked side by side.”

The cold November night I visited Presa House to view Latent Blatant, on the eve of the opening reception, I saw her son going from room to room, happily at ease in a gallery that feels like home, with his mother’s portraits adorning the walls. “He allowed me to be an artist and learn about accepting and processing my emotions of this body,” Rawls confessed, “I want him to feel this way about himself, so I need to learn how to appreciate and nurture myself.”

Rawls’s lines and textures reflect the twists, turns, stops, and starts that make up a woman’s life. When we connect the dots, the path becomes clear. In her essay Talking Back, bell hooks writes: “Moving from silence to speech is for the oppressed, the colonized, the exploited…a gesture of defiance that heals, that makes new life and new growth possible.”

How would my relationship with my body have changed if I had been presented earlier with more work by artists like Aguilar, Saville, or Rawls? The night I met her, we spent time talking about her inspiration and process, and she shared backstory on the mobile sculpture suspended in the middle of the gallery’s back room. Tejiendo Lágrimas Entre Empatía y Comprensión (Knitting Tears Between Empathy and Understanding) is the crown of the exhibition.

Walking around the mobile creates enough momentum to set it into motion; combined with the illumination of the gallery lights, it projects watery shadows of color through each cut-out figure. Rawls laser cut the acrylic pieces at Brownsville Public Library and they make a pleasant clacking sound reminiscent of the sounds the marks must make when she paints.

If Latent Blatant is, according to exhibition text, “a visual dialogue of self-acceptance, self-expression, the nuanced depth of personal experience, and the truths about oneself that are often masked and elude words,” then these moments I experience within the exhibition and while writing this essay must mean I, too, am finding my way.

A few days after Latent Blatant opens, the sun finally peeks out from behind days of gray skies. Presa House shares a video of the mobile, in daylight with the clouds now cleared, and we see how bright San Anto sunbeams streaming through the windows have brought Tejiendo LágrimasEntre Empatía y Comprensión to life. The clear acrylic bodies and dots suddenly, beautifully beam impressions along the walls, dancing colorful circles around the gallery.

I see: Rawls’s figures escaping the confines of their physical boundaries and gracefully erupting into cascades of light confetti. I believe: we are waking up to the miracle of our own bodies, no matter our weight, with empathy and understanding. I hope: we keep beaming light into the world that is vast and sacred enough to fit us all.

Sam Rawls: Latent Blatant is on view at Presa House Gallery through December 23, 2023. The Closing Reception will be held Saturday, December 23, 2023.

Edited by Rigoberto Luna. Photos Courtesy of the Artist and Photographer Jenelle Esparza.